Corruption - A social disease (Part 174): Namibia at the cross roads

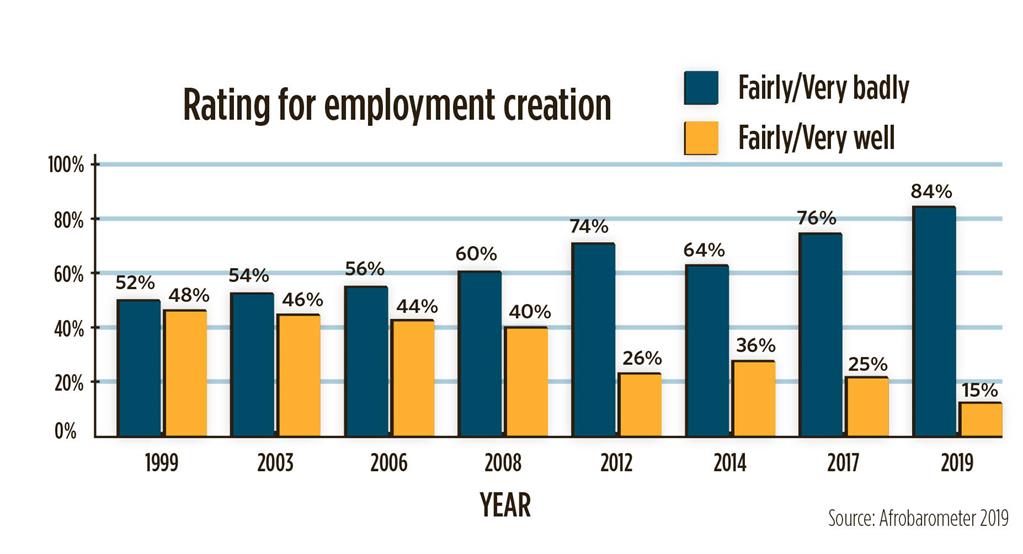

Public perceptions about how well government is handling job creation has decreased since 1999 as is evident in data reported by the Afrobarometer in 2019.

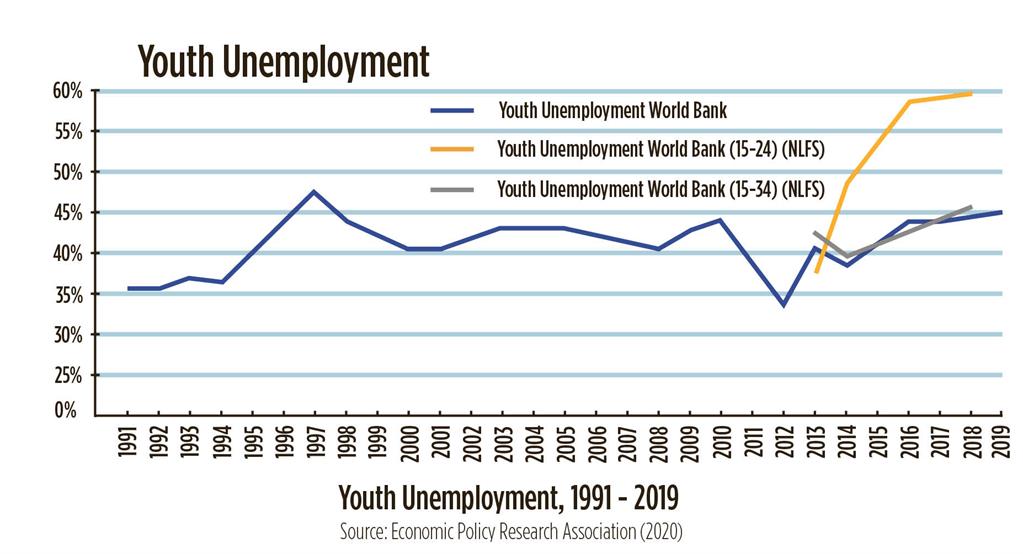

An expected increase in unemployment, refer to the increase in youth unemployment since 2013, and an increase in private debt, which is one of the most prominent indicators of severe economic depression, do not leave much optimism for employment and entrepreneurship.

Unemployment has reached levels almost beyond the means of the government to assist the unemployed.

Government has introduced several job-creation projects, but most have been unsustainable due to very limited efficient management (e.g. the Green schemes), financial prudence, and inadequate competitiveness of the products and services these projects were intended to provide.

An increase in unemployment, especially youth unemployment, and to be more specific among qualified people, can be an indication that given all contributors mentioned, it is highly probable that Namibia’s education system is not preparing the youth for the labour market.

With a small population relative to Namibia’s neighbours and 60% youth unemployment, is Namibia’s entrepreneurial opportunities adequate for people to earn a decent living? Does Namibia need more state intervention to control the labour market?

STATE CONTROL AND INTERVENTION

The overarching trend of state control and state intervention is probably one of the most critical enablers/drivers that has brought Namibia to the cross-roads of much-needed policy turnaround - in investment, public service delivery, and unemployment.

This trend is contrary to global trends in public and project governance. For example, value added governance, e-governance and network governance have the common denominator to minimise the role of government.

With increased fusion of the role of public and private sector as manifested in Public Private Enterprises (PPEs), the role of central governments is outdated. Governments are increasingly become only facilitators of social dialogue about national policy, not the main drivers of policy.

The new interest in local government level politics and service delivery prior to the 2020 elections, is demonstrative of the trend of self-governance and the benefits pertaining thereto. Potholes in Eros being repaired by community volunteers is an example of this.

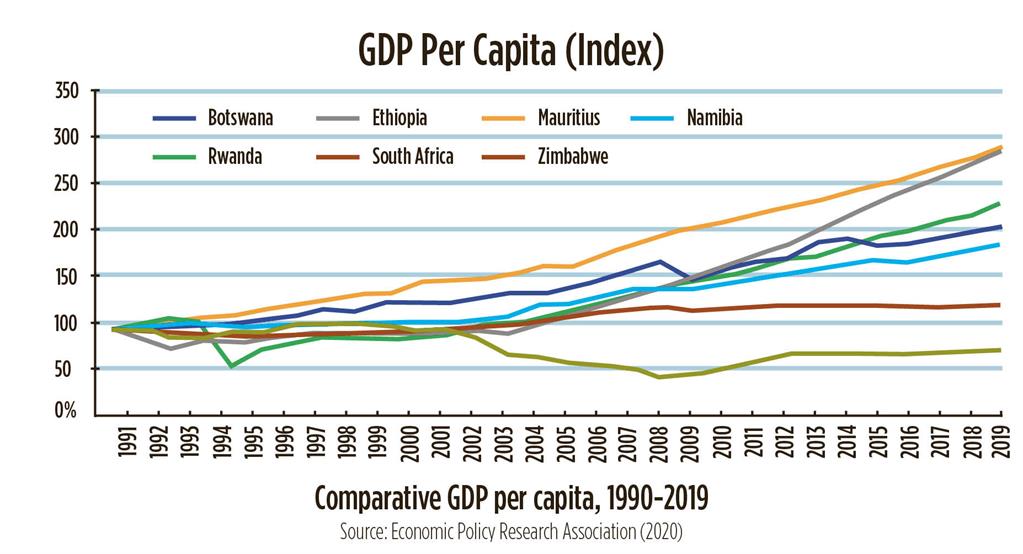

From the plotting of performance of some economies across Africa over the past three decades, it can be deduced that excessive state control and intervention is counterproductive (see data on comparative GDP per capita for 1990-2019).

The continent’s success stories have been countries that have liberalised, embraced the free market and private sector, and implemented structural changes. Zimbabwe and South Africa have taken the opposite path and are lagging in the region.

Mauritius, Botswana, Rwanda and Ethiopia are the success stories. And while Namibia has been a mid-range performer, the country now seems increasingly more inclined to turn towards excessive state-controlled policies with many similarities to Zimbabwe and South Africa, rather than copying the success stories.

When it comes to government/public spending, Namibia has the third best-resourced government in the world relative to the size of our economy (third highest tax-to-GDP ratio in the world). However, despite enormous resources, our government still spends between N$8 and N$10 billion a year more than the revenue collected, an ever-increasing unsustainable situation.

Government is unlikely to stimulate growth through more spending during the next three to five years. In addition to the latter, NEEEB will most probably negatively affect employment creation, growth in business, profits and public revenue (Bartsch, Coetzee, Smith & De Klerk).

A contributor to public spending, by all governments is that public debt is rolled over from year to year because of quantitative easing by central banks, e.g. the Bank of Namibia. Maturities are extended and public debt is artificially (mis)managed by quantitative easing or ‘printing’ more money.

Like with corruption and public service delivery, one of the sub-trends that should be read together with the trend of state control and intervention is the increase in executive power and discretion, with very limited checks and balances.

For example, amendments to the Marine Resources Act enabled the Minister of Fisheries and Marine Resources to provide the largest quotas to Fishcor, which disadvantaged other fishing companies. The latter legislation was central in facilitating Fishrot. The previous Minister of Justice and Attorney General, Sacky Shangala played a critical role in amending this legislation thereby 'legalising corruption’. The latter is one symptom of a state penetrated by corruption and permeated by systemic corruption, when laws are amended to legalise, enforce and facilitate corruption. When laws are inadequate to protect citizens and are used to the disadvantage of most citizens, similar to Apartheid legislation, it can be an indicator of an illegitimate government, which does not represent the will of the people.

It has been reported by Namibian Sun that a plan is afoot to bar the media and the public from access to certain court proceeding and documents. This is perceived by some as an attempt to protect powerful individuals such as the political connected and business elite from scrutiny. Any such plan contradicts the principles enshrined in the Access to Information Bill, which will provide increased transparency.

Is this judicial move purely accidental after the Fishrot case and the Kora music awards fiasco? Is this illustrative of deliberate, undue political influence over the judiciary to pave the way for concealing corruption by the elite?

SYNTHESIS

Trends in lagging investment; corruption and public service delivery; unemployment, and state control and state intervention do not only overlap, but are interrelated, interconnected and interdependent.

If state control and intervention increase, it can increasingly conceal unchecked corruption and money laundering, and increase uncontained executive power. An increase in state control can also manifest in increasing regulatory control over money entering and leaving Namibia, reducing investment and indirectly also reducing employment stimulation.

These trends should be viewed in conjunction and require constant monitoring of the impact on each other.

Fixed capital formation decreased from 32.5% to 26.5%, net direct investment decreased from 7.2% to 2%, and further decreased to minus 1% in 2013. Corruption perception ratings by Transparency International (TI) decreased from 4.5 to 4.2 and approval for employment creation decreased from 48% to 15%.

These are all significant decreases.

It could be that decreases in investment and increases in unemployment by 2010-2012 were still part of the aftermath of the global recession of 2008. However, policies such as NEEEF and the Namibia Investment Promotion Policy have caused an outflow of capital since 2014.

The years 2014/15 is noteworthy because it was when the first term of the third President of Namibia commenced.

The improvement in TI corruption indices can be attributed to some extent to the President's and the First Lady's declaration of their assets during 2014/2015. There was also much optimism about the Harambee Prosperity Plan and the highest support (85%) for a President in an election in 2014.

Separating contributors to corruption as individual variables to determine if correlation exist between a variable and perception ratings of specific years is not possible with fool-proof certainty. However, it can be plausible to some degree.

Party politics and specific that of the ruling party and its inability to unlearn its politics of state control and intervention is one of the main drivers that have brought Namibia to its cross roads. Namibia can however change towards more sustainable governance. Will it happen?

Based on existing trends, it does not seem probable. However, history is not about the past, it is about change. Party politics and the power of people to change things from the bottom upwards, can be catalysts for change.

Irrespective of who governs the country, let us be accountable for our future and get involved in self-governance, such as service delivery at local government. At ‘pothole level' we can make a difference and see much better where we are heading.

(This is the final part in the series of articles subtitled Namibia at the cross roads. The column will continue to be published in Market Watch as new articles are written by die author.)

References

Bartsch, A., Coetzee, J.J., Smith, J. & De Klerk, E. (2020). Economic Policy Research Association: Analysis of the Latest Version of the New Equitable Economic Empowerment Bill.

Beukes, J. (2021). Damaseb’s secret courts plan rejected. Namibian Sun, 8 February.

[email protected]

An expected increase in unemployment, refer to the increase in youth unemployment since 2013, and an increase in private debt, which is one of the most prominent indicators of severe economic depression, do not leave much optimism for employment and entrepreneurship.

Unemployment has reached levels almost beyond the means of the government to assist the unemployed.

Government has introduced several job-creation projects, but most have been unsustainable due to very limited efficient management (e.g. the Green schemes), financial prudence, and inadequate competitiveness of the products and services these projects were intended to provide.

An increase in unemployment, especially youth unemployment, and to be more specific among qualified people, can be an indication that given all contributors mentioned, it is highly probable that Namibia’s education system is not preparing the youth for the labour market.

With a small population relative to Namibia’s neighbours and 60% youth unemployment, is Namibia’s entrepreneurial opportunities adequate for people to earn a decent living? Does Namibia need more state intervention to control the labour market?

STATE CONTROL AND INTERVENTION

The overarching trend of state control and state intervention is probably one of the most critical enablers/drivers that has brought Namibia to the cross-roads of much-needed policy turnaround - in investment, public service delivery, and unemployment.

This trend is contrary to global trends in public and project governance. For example, value added governance, e-governance and network governance have the common denominator to minimise the role of government.

With increased fusion of the role of public and private sector as manifested in Public Private Enterprises (PPEs), the role of central governments is outdated. Governments are increasingly become only facilitators of social dialogue about national policy, not the main drivers of policy.

The new interest in local government level politics and service delivery prior to the 2020 elections, is demonstrative of the trend of self-governance and the benefits pertaining thereto. Potholes in Eros being repaired by community volunteers is an example of this.

From the plotting of performance of some economies across Africa over the past three decades, it can be deduced that excessive state control and intervention is counterproductive (see data on comparative GDP per capita for 1990-2019).

The continent’s success stories have been countries that have liberalised, embraced the free market and private sector, and implemented structural changes. Zimbabwe and South Africa have taken the opposite path and are lagging in the region.

Mauritius, Botswana, Rwanda and Ethiopia are the success stories. And while Namibia has been a mid-range performer, the country now seems increasingly more inclined to turn towards excessive state-controlled policies with many similarities to Zimbabwe and South Africa, rather than copying the success stories.

When it comes to government/public spending, Namibia has the third best-resourced government in the world relative to the size of our economy (third highest tax-to-GDP ratio in the world). However, despite enormous resources, our government still spends between N$8 and N$10 billion a year more than the revenue collected, an ever-increasing unsustainable situation.

Government is unlikely to stimulate growth through more spending during the next three to five years. In addition to the latter, NEEEB will most probably negatively affect employment creation, growth in business, profits and public revenue (Bartsch, Coetzee, Smith & De Klerk).

A contributor to public spending, by all governments is that public debt is rolled over from year to year because of quantitative easing by central banks, e.g. the Bank of Namibia. Maturities are extended and public debt is artificially (mis)managed by quantitative easing or ‘printing’ more money.

Like with corruption and public service delivery, one of the sub-trends that should be read together with the trend of state control and intervention is the increase in executive power and discretion, with very limited checks and balances.

For example, amendments to the Marine Resources Act enabled the Minister of Fisheries and Marine Resources to provide the largest quotas to Fishcor, which disadvantaged other fishing companies. The latter legislation was central in facilitating Fishrot. The previous Minister of Justice and Attorney General, Sacky Shangala played a critical role in amending this legislation thereby 'legalising corruption’. The latter is one symptom of a state penetrated by corruption and permeated by systemic corruption, when laws are amended to legalise, enforce and facilitate corruption. When laws are inadequate to protect citizens and are used to the disadvantage of most citizens, similar to Apartheid legislation, it can be an indicator of an illegitimate government, which does not represent the will of the people.

It has been reported by Namibian Sun that a plan is afoot to bar the media and the public from access to certain court proceeding and documents. This is perceived by some as an attempt to protect powerful individuals such as the political connected and business elite from scrutiny. Any such plan contradicts the principles enshrined in the Access to Information Bill, which will provide increased transparency.

Is this judicial move purely accidental after the Fishrot case and the Kora music awards fiasco? Is this illustrative of deliberate, undue political influence over the judiciary to pave the way for concealing corruption by the elite?

SYNTHESIS

Trends in lagging investment; corruption and public service delivery; unemployment, and state control and state intervention do not only overlap, but are interrelated, interconnected and interdependent.

If state control and intervention increase, it can increasingly conceal unchecked corruption and money laundering, and increase uncontained executive power. An increase in state control can also manifest in increasing regulatory control over money entering and leaving Namibia, reducing investment and indirectly also reducing employment stimulation.

These trends should be viewed in conjunction and require constant monitoring of the impact on each other.

Fixed capital formation decreased from 32.5% to 26.5%, net direct investment decreased from 7.2% to 2%, and further decreased to minus 1% in 2013. Corruption perception ratings by Transparency International (TI) decreased from 4.5 to 4.2 and approval for employment creation decreased from 48% to 15%.

These are all significant decreases.

It could be that decreases in investment and increases in unemployment by 2010-2012 were still part of the aftermath of the global recession of 2008. However, policies such as NEEEF and the Namibia Investment Promotion Policy have caused an outflow of capital since 2014.

The years 2014/15 is noteworthy because it was when the first term of the third President of Namibia commenced.

The improvement in TI corruption indices can be attributed to some extent to the President's and the First Lady's declaration of their assets during 2014/2015. There was also much optimism about the Harambee Prosperity Plan and the highest support (85%) for a President in an election in 2014.

Separating contributors to corruption as individual variables to determine if correlation exist between a variable and perception ratings of specific years is not possible with fool-proof certainty. However, it can be plausible to some degree.

Party politics and specific that of the ruling party and its inability to unlearn its politics of state control and intervention is one of the main drivers that have brought Namibia to its cross roads. Namibia can however change towards more sustainable governance. Will it happen?

Based on existing trends, it does not seem probable. However, history is not about the past, it is about change. Party politics and the power of people to change things from the bottom upwards, can be catalysts for change.

Irrespective of who governs the country, let us be accountable for our future and get involved in self-governance, such as service delivery at local government. At ‘pothole level' we can make a difference and see much better where we are heading.

(This is the final part in the series of articles subtitled Namibia at the cross roads. The column will continue to be published in Market Watch as new articles are written by die author.)

References

Bartsch, A., Coetzee, J.J., Smith, J. & De Klerk, E. (2020). Economic Policy Research Association: Analysis of the Latest Version of the New Equitable Economic Empowerment Bill.

Beukes, J. (2021). Damaseb’s secret courts plan rejected. Namibian Sun, 8 February.

[email protected]

Kommentaar

Republikein

Geen kommentaar is op hierdie artikel gelaat nie