Corruption: Nam loses shine in region

Namibia is now regarded as the 52nd least corrupt country out of 180 tracked by Transparency International worldwide.

Jo-Maré Duddy – Namibia has dropped one spot in Sub-Saharan Africa in terms of score on Transparency International’s latest Corruption Perception Index (CPI).

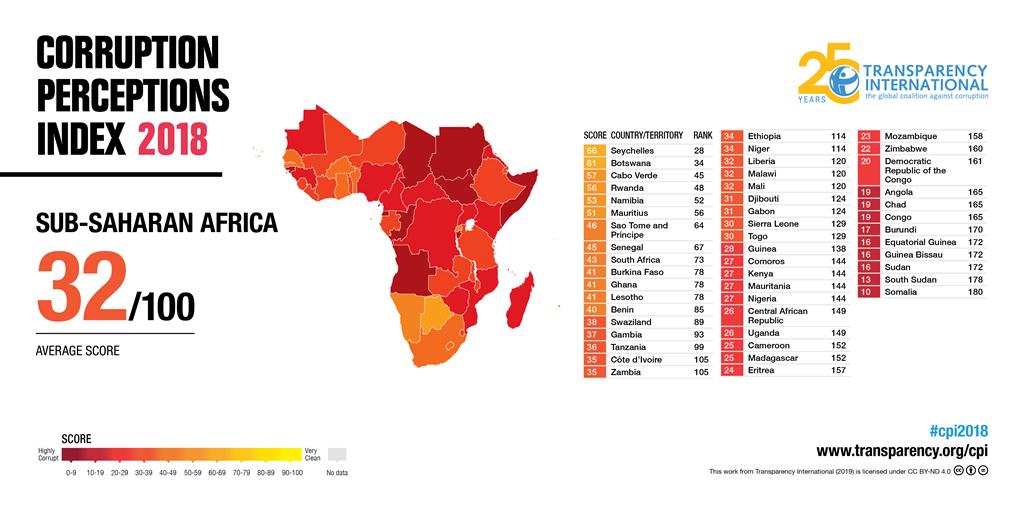

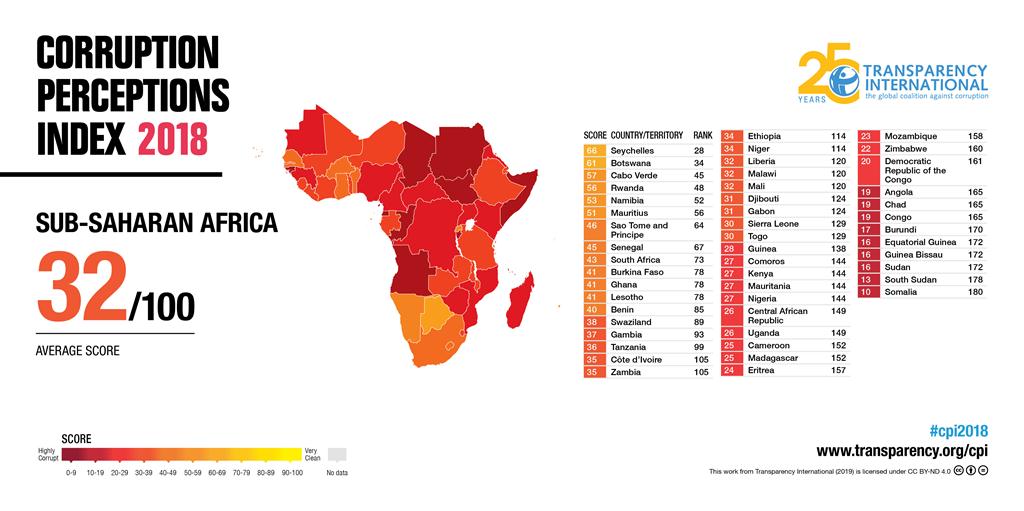

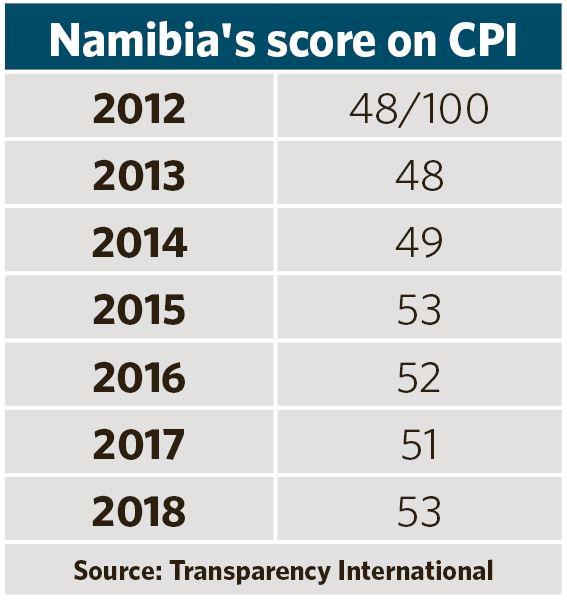

According to the 2018 CPI, released yesterday, Namibia scored 53 out of a possible 100. Although this is an improvement on the 51 points achieved on the 2017 CPI, the latest score places Namibia fifth in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to fourth on the previous index.

In 2018, Namibia ranked behind Seychelles (score 66), Botswana (61), Cape Verde (57) and Rwanda (56). In 2017, the country was behind Seychelles (60), Botswana (61), as well as Cape Verde and Rwanda – both with 55 points.

Zero on the CPI score slide means a country is highly corrupt, while 100 indicates a country is “very clean”.

The improvement in Namibia’s overall score in 2018 meant the country is now regarded as the 52nd least corrupt country out of 180 tracked by Transparency International (TI) worldwide. In 2017, Namibia was ranked 53rd. Seychelles with its top score on the continent was ranked 28th on the 2018 CPI.

Namibia’s performance on the latest CPI is better than the world and regional average. The global average score is 43 and more than two-thirds of the countries included in the 2018 CPI falls into this category. The average score for Sub-Saharan Africa is 32.

“With an average score of just 32, Sub-Saharan Africa is the lowest scoring region on the index, followed closely by Eastern Europe and Central Asia, with an average score of 35,” TI says.

Africa

The global watchdog says the 2018 CPI “presents a largely gloomy picture for Africa” with only eight of 49 countries which scored more than 43. “Despite commitments from African leaders in declaring 2018 as the African Year of Anti-Corruption, this has yet to translate into concrete progress,” TI elaborates.

Sub-Saharan Africa remains a region of stark political and socio-economic contrasts and many longstanding challenges, the watchdog says.

“While a large number of countries have adopted democratic principles of governance, several are still governed by authoritarian and semi-authoritarian leaders. Autocratic regimes, civil strife, weak institutions and unresponsive political systems continue to undermine anti-corruption efforts,” TI says.

According to TI, top scorers Seychelles and Botswana have a few attributes in common. “Both have relatively well-functioning democratic and governance systems, which help contribute to their scores. However, these countries are the exception rather than the norm in a region where most democratic principles are at risk and corruption is high,” TI says.

Many low performing countries have several commonalties, including few political rights, limited press freedoms and a weak rule of law, TI continues.

“In these countries, laws often go unenforced and institutions are poorly resourced with little ability to handle corruption complaints. In addition, internal conflict and unstable governance structures contribute to high rates of corruption.”

Progress

Ivory Coast and Senegal were, for the second year in a row, among the significant improvers on the CPI. In the last six years, Ivory Coast moved from 27 points in 2013 to 35 points in 2018, while Senegal moved from 36 points in 2012 to 45 points in 2018.

“These gains may be attributed to the positive consequences of legal, policy and institutional reforms undertaken in both countries as well as political will in the fight against corruption demonstrated by their respective leaders,” TI says.

Angola

With a score of 19, Angola increased four points since 2015.

“President João Lourenço has been championing reforms and tackling corruption since he took office in 2017, firing over 60 government officials, including Isabel dos Santos, the daughter of his predecessor, Eduardo Dos Santos. Recently, the former president’s son, Jose Filomeno dos Santos, was charged with making a fraudulent US$500 million transaction from Angola's sovereign wealth fund,” TI says.

However, the problem of corruption in Angolan goes far beyond the Dos Santos family, TI points out. “It is very important that the current leadership shows consistency in the fight against corruption in Angola.”

South Africa

With a score of 43, South Africa remained unchanged on the CPI since 2017.

“Under president Cyril Ramaphosa, the administration has taken additional steps to address anti-corruption on a national level, including through the work of the Anti-Corruption Inter-Ministerial Committee. Although the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS) has been in place for years, the current government continues to build momentum for the strategy by soliciting public input,” TI says.

Citizen engagement on social media and various commissions of inquiry into corruption abuses are also positive steps in South Africa, it says.

In both Kenya and South Africa, citizen engagement in the fight against corruption is crucial, TI says.

“For example, social media has played a big role in driving public conversation around corruption. The rise of mobile technology means ordinary citizens in many countries now have instant access to information, and an ability to voice their opinions in a way that previous generations did not.”

According to the 2018 CPI, released yesterday, Namibia scored 53 out of a possible 100. Although this is an improvement on the 51 points achieved on the 2017 CPI, the latest score places Namibia fifth in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to fourth on the previous index.

In 2018, Namibia ranked behind Seychelles (score 66), Botswana (61), Cape Verde (57) and Rwanda (56). In 2017, the country was behind Seychelles (60), Botswana (61), as well as Cape Verde and Rwanda – both with 55 points.

Zero on the CPI score slide means a country is highly corrupt, while 100 indicates a country is “very clean”.

The improvement in Namibia’s overall score in 2018 meant the country is now regarded as the 52nd least corrupt country out of 180 tracked by Transparency International (TI) worldwide. In 2017, Namibia was ranked 53rd. Seychelles with its top score on the continent was ranked 28th on the 2018 CPI.

Namibia’s performance on the latest CPI is better than the world and regional average. The global average score is 43 and more than two-thirds of the countries included in the 2018 CPI falls into this category. The average score for Sub-Saharan Africa is 32.

“With an average score of just 32, Sub-Saharan Africa is the lowest scoring region on the index, followed closely by Eastern Europe and Central Asia, with an average score of 35,” TI says.

Africa

The global watchdog says the 2018 CPI “presents a largely gloomy picture for Africa” with only eight of 49 countries which scored more than 43. “Despite commitments from African leaders in declaring 2018 as the African Year of Anti-Corruption, this has yet to translate into concrete progress,” TI elaborates.

Sub-Saharan Africa remains a region of stark political and socio-economic contrasts and many longstanding challenges, the watchdog says.

“While a large number of countries have adopted democratic principles of governance, several are still governed by authoritarian and semi-authoritarian leaders. Autocratic regimes, civil strife, weak institutions and unresponsive political systems continue to undermine anti-corruption efforts,” TI says.

According to TI, top scorers Seychelles and Botswana have a few attributes in common. “Both have relatively well-functioning democratic and governance systems, which help contribute to their scores. However, these countries are the exception rather than the norm in a region where most democratic principles are at risk and corruption is high,” TI says.

Many low performing countries have several commonalties, including few political rights, limited press freedoms and a weak rule of law, TI continues.

“In these countries, laws often go unenforced and institutions are poorly resourced with little ability to handle corruption complaints. In addition, internal conflict and unstable governance structures contribute to high rates of corruption.”

Progress

Ivory Coast and Senegal were, for the second year in a row, among the significant improvers on the CPI. In the last six years, Ivory Coast moved from 27 points in 2013 to 35 points in 2018, while Senegal moved from 36 points in 2012 to 45 points in 2018.

“These gains may be attributed to the positive consequences of legal, policy and institutional reforms undertaken in both countries as well as political will in the fight against corruption demonstrated by their respective leaders,” TI says.

Angola

With a score of 19, Angola increased four points since 2015.

“President João Lourenço has been championing reforms and tackling corruption since he took office in 2017, firing over 60 government officials, including Isabel dos Santos, the daughter of his predecessor, Eduardo Dos Santos. Recently, the former president’s son, Jose Filomeno dos Santos, was charged with making a fraudulent US$500 million transaction from Angola's sovereign wealth fund,” TI says.

However, the problem of corruption in Angolan goes far beyond the Dos Santos family, TI points out. “It is very important that the current leadership shows consistency in the fight against corruption in Angola.”

South Africa

With a score of 43, South Africa remained unchanged on the CPI since 2017.

“Under president Cyril Ramaphosa, the administration has taken additional steps to address anti-corruption on a national level, including through the work of the Anti-Corruption Inter-Ministerial Committee. Although the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS) has been in place for years, the current government continues to build momentum for the strategy by soliciting public input,” TI says.

Citizen engagement on social media and various commissions of inquiry into corruption abuses are also positive steps in South Africa, it says.

In both Kenya and South Africa, citizen engagement in the fight against corruption is crucial, TI says.

“For example, social media has played a big role in driving public conversation around corruption. The rise of mobile technology means ordinary citizens in many countries now have instant access to information, and an ability to voice their opinions in a way that previous generations did not.”

Kommentaar

Republikein

Geen kommentaar is op hierdie artikel gelaat nie