Swapo sacrifices social cohesion

Recent political developments indicate that Namibian society is further away from “unity in diversity” as it had been at Independence and is deeply divided.

Jo-Maré Duddy – “After three decades in political power, Swapo has wasted social capital and sacrificed the asset of social cohesion for short-term individual gains of a new elite.”

That is the conclusion Namibian-born renowned political scientist Prof Henning Melber draws in his latest research paper, ““One Namibia, One Nation”? Social Cohesion under a Liberation Movement as Government in Decline”, published in the Vienna Journal of African Studies. Among others, Melber currently is an associate at the Nordic Africa Institute.

Social cohesion has been linked to positive economic performance in a country, as well as stronger consensus, support for democracy, stability and conflict prevention in times of crisis, and better health and livelihood outcomes, his paper explains.

Melber says Namibia has been widely perceived as a successful case of negotiated independence, governed since 1990 by the former liberation movement, Swapo.

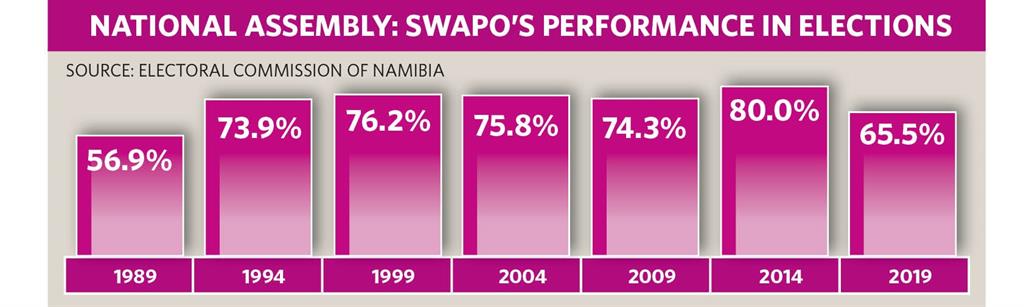

“For a quarter of a century the movement turned party expanded its political dominance. Of lately, this hegemony showed cracks.

“The credibility and reputation, and hence the trust into those in government has been damaged due to a number of contributing factors. This has also resulted in a decline of social cohesion as part of the slippery road in so-called nation building,” he elaborates.

SYMPTOMS OF SOCIAL ANOMY

Melber points out that Namibia continues to rank in all comparative surveys of African states among the top five performers in terms of good governance on the continent. However, these favourable assessments go hand in hand with symptoms of social anomy.

“The relative political stability contrasts with the deprived living conditions of the majority of the population in one of the most unequal societies of this world,” he says.

Inequalities, trust and identities are substantive components of social cohesion, Melber agrees with other experts.

In marked contrast to the rather bumpy rides of South African presidents in the succession of Nelson Mandela, Swapo’s three candidates in the first five presidential elections (1994 to 2014) received massive approval among the electorate by garnering even more votes than the party, Melber says.

“The electoral conformism with one party in what has been considered as by and large free and fair elections, as well as the social capital (i.e. trust) vested in the party’s presidential candidates, in combination with the reputation of having liberated the country from colonial minority rule, suggested a high degree of social cohesion,” he remarks.

GENERATIONAL DIVIDE

Swapo was “almost insurmountable” for any political opposition - even more so, when such opposition for decades was hardly any alternative to the party in power, he adds.

According to Melber, founding president Sam Nujoma was viewed as a leader who brought about peace, his successor Hifikepunye Pohamba was synonymous with stability and current president Hage Geingob was tasked to ensure prosperity.

Even the most durable party-based regimes needs to bridge a generational divide, he says.

“At a moment in time where the expiry date for most first generation Swapo activists with struggle credentials approaches, the heroic narrative turns into an anachronism.”

National reconciliation became the programmatic slogan for a co-optation strategy based on the structural legacy of settler colonial minority rule and its corresponding property relations with Swapo’s strategy becoming one of facilitating, as cultural entrepreneur, an elite pact, he explains.

NEW ELITE

The reconfiguration of the socio-economic landscape, based on control over the political commanding heights of the Namibian state, operated through the vehicles of Affirmative Action (AA) and Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), a redistributive strategy based on the co-optation of a new elite into the old socio-economic structures, Melber says.

National reconciliation of such a class character could only be “an elite discourse bent on maintaining the legitimacy of the state and responding to the inherent contradictions that characterise Swapo’s own anti-colonial discourse, he quotes Prof André du Pisani, a Namibian political scientist.

Public procurement and other outsourcing activities by those in control of state agencies turned AA and BEE into a self-rewarding scheme based on struggle credentials and credits among the activists of the liberation movement, Melber says.

“Through such practices, the skewed class character of Namibia’s society changed little. But co-optation into the ruling segments of an existing socioeconomic system is very different from social transformation,” he says.

Melber continues: “The ongoing exclusion of the impoverished and marginalised from the benefits of the country’s wealth and resources is no longer only the result of the structural legacy of Apartheid, as is so conveniently claimed by the new postcolonial elite. To that extent the official position, which continues to put the blame squarely on settler colonialism alone, is misleading and shying away from the real issues at stake.”

Policy turned in the main into self-enrichment within an unchallenged system of crude capitalism and related class structures. The lifestyle enjoyed by a tiny (previously almost exclusively white) elite continued to contrast with the poverty of a majority of the people.

THE NAMIBIAN HOUSE

“The Namibian House” became Geingob’s mantra, meant to recognise the country’s need for meaningful social cohesion and to transcend ethnicity. “To be successful, however, it requires more than words,” Melber says.

Geingob’s Harambee Prosperity Plan – the first launched in 2016, followed by a second one in 2021 - offered a wide range of promises, including a significant reduction in poverty levels.

“The illusionary wishful thinking was based on an anticipated annual economic growth rate of 7% at a time, when the economic prospects already signalled tough times and rough waters ahead,” Melber says. Namibia’s current recessionary cycle started in 2016.

A comparison of the data and ranking in the United Nation’s Human Development Report (HDR) of 2020 with that of 2015 confirms “the sobering lack of progress during Geingob’s first term in office,” he says.

Melber elaborates: “Ranked 130, Namibia’s HDI [Human Development Index] dropped slightly, while – as a minor comfort – the inequality adjusted HDI “only” declined by 14 ranks (the eighth biggest difference of all countries).

“However, the income discrepancy maintained a top position: the richest 1% in society had an income share of 21.5%, the richest 10% of 47.3%, while the poorest 40% had an income share of 8.6%. A rather drastic contrast to the “prosperity for all” mantra, underlined by the second highest Gini-coefcient (measuring income inequality) with 59.1 – only topped by neighbouring South Africa.”

Despite all rhetoric under the Geingob administration, Namibia remains among the most unequal societies in the world, Melber says.

‘WEAR AND TEAR’

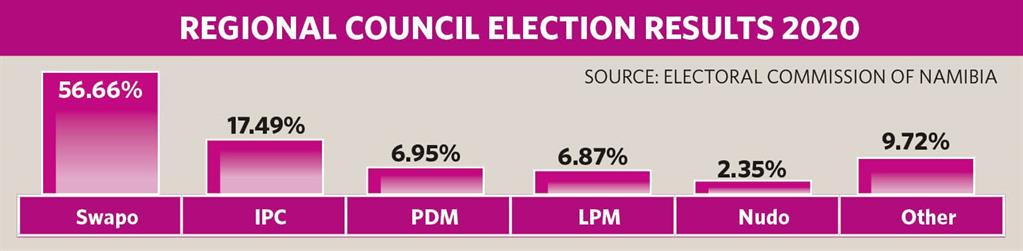

Ordinary Namibians were aware of the lack of improvements, Melber says, and their discontent is evident from recent election results.

“The first signs of wear and tear in the Swapo hegemony became visible with the elections in November 2019 and November 2020, when dissatisfaction translated into a first decline of Swapo’s political control over the country’s governance.”

According to Melber: “In the absence of a more efficient policy coherence, which would be able to link the narrative of the Swapo government(s) with material delivery for the majority of the people and dismissing sufficient recognition of multiple identities in terms of political, cultural and ethnic background as well as other forms of deviating behaviour from the established norms and values defined by those in political power, social cohesion in Namibia remains superficial and less anchored than it claims to be.”

* Prof Henning Melber is also affiliated as director emeritus of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, he is an extraordinary professor at the University of Pretoria and the University of the Free State, a senior research fellow at the Institute for Commonwealth Studies/University of London, as well as the president of the European Association of Development Research and Trading Institutes (EADI). He has been a member of Swapo since 1974.

That is the conclusion Namibian-born renowned political scientist Prof Henning Melber draws in his latest research paper, ““One Namibia, One Nation”? Social Cohesion under a Liberation Movement as Government in Decline”, published in the Vienna Journal of African Studies. Among others, Melber currently is an associate at the Nordic Africa Institute.

Social cohesion has been linked to positive economic performance in a country, as well as stronger consensus, support for democracy, stability and conflict prevention in times of crisis, and better health and livelihood outcomes, his paper explains.

Melber says Namibia has been widely perceived as a successful case of negotiated independence, governed since 1990 by the former liberation movement, Swapo.

“For a quarter of a century the movement turned party expanded its political dominance. Of lately, this hegemony showed cracks.

“The credibility and reputation, and hence the trust into those in government has been damaged due to a number of contributing factors. This has also resulted in a decline of social cohesion as part of the slippery road in so-called nation building,” he elaborates.

SYMPTOMS OF SOCIAL ANOMY

Melber points out that Namibia continues to rank in all comparative surveys of African states among the top five performers in terms of good governance on the continent. However, these favourable assessments go hand in hand with symptoms of social anomy.

“The relative political stability contrasts with the deprived living conditions of the majority of the population in one of the most unequal societies of this world,” he says.

Inequalities, trust and identities are substantive components of social cohesion, Melber agrees with other experts.

In marked contrast to the rather bumpy rides of South African presidents in the succession of Nelson Mandela, Swapo’s three candidates in the first five presidential elections (1994 to 2014) received massive approval among the electorate by garnering even more votes than the party, Melber says.

“The electoral conformism with one party in what has been considered as by and large free and fair elections, as well as the social capital (i.e. trust) vested in the party’s presidential candidates, in combination with the reputation of having liberated the country from colonial minority rule, suggested a high degree of social cohesion,” he remarks.

GENERATIONAL DIVIDE

Swapo was “almost insurmountable” for any political opposition - even more so, when such opposition for decades was hardly any alternative to the party in power, he adds.

According to Melber, founding president Sam Nujoma was viewed as a leader who brought about peace, his successor Hifikepunye Pohamba was synonymous with stability and current president Hage Geingob was tasked to ensure prosperity.

Even the most durable party-based regimes needs to bridge a generational divide, he says.

“At a moment in time where the expiry date for most first generation Swapo activists with struggle credentials approaches, the heroic narrative turns into an anachronism.”

National reconciliation became the programmatic slogan for a co-optation strategy based on the structural legacy of settler colonial minority rule and its corresponding property relations with Swapo’s strategy becoming one of facilitating, as cultural entrepreneur, an elite pact, he explains.

NEW ELITE

The reconfiguration of the socio-economic landscape, based on control over the political commanding heights of the Namibian state, operated through the vehicles of Affirmative Action (AA) and Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), a redistributive strategy based on the co-optation of a new elite into the old socio-economic structures, Melber says.

National reconciliation of such a class character could only be “an elite discourse bent on maintaining the legitimacy of the state and responding to the inherent contradictions that characterise Swapo’s own anti-colonial discourse, he quotes Prof André du Pisani, a Namibian political scientist.

Public procurement and other outsourcing activities by those in control of state agencies turned AA and BEE into a self-rewarding scheme based on struggle credentials and credits among the activists of the liberation movement, Melber says.

“Through such practices, the skewed class character of Namibia’s society changed little. But co-optation into the ruling segments of an existing socioeconomic system is very different from social transformation,” he says.

Melber continues: “The ongoing exclusion of the impoverished and marginalised from the benefits of the country’s wealth and resources is no longer only the result of the structural legacy of Apartheid, as is so conveniently claimed by the new postcolonial elite. To that extent the official position, which continues to put the blame squarely on settler colonialism alone, is misleading and shying away from the real issues at stake.”

Policy turned in the main into self-enrichment within an unchallenged system of crude capitalism and related class structures. The lifestyle enjoyed by a tiny (previously almost exclusively white) elite continued to contrast with the poverty of a majority of the people.

THE NAMIBIAN HOUSE

“The Namibian House” became Geingob’s mantra, meant to recognise the country’s need for meaningful social cohesion and to transcend ethnicity. “To be successful, however, it requires more than words,” Melber says.

Geingob’s Harambee Prosperity Plan – the first launched in 2016, followed by a second one in 2021 - offered a wide range of promises, including a significant reduction in poverty levels.

“The illusionary wishful thinking was based on an anticipated annual economic growth rate of 7% at a time, when the economic prospects already signalled tough times and rough waters ahead,” Melber says. Namibia’s current recessionary cycle started in 2016.

A comparison of the data and ranking in the United Nation’s Human Development Report (HDR) of 2020 with that of 2015 confirms “the sobering lack of progress during Geingob’s first term in office,” he says.

Melber elaborates: “Ranked 130, Namibia’s HDI [Human Development Index] dropped slightly, while – as a minor comfort – the inequality adjusted HDI “only” declined by 14 ranks (the eighth biggest difference of all countries).

“However, the income discrepancy maintained a top position: the richest 1% in society had an income share of 21.5%, the richest 10% of 47.3%, while the poorest 40% had an income share of 8.6%. A rather drastic contrast to the “prosperity for all” mantra, underlined by the second highest Gini-coefcient (measuring income inequality) with 59.1 – only topped by neighbouring South Africa.”

Despite all rhetoric under the Geingob administration, Namibia remains among the most unequal societies in the world, Melber says.

‘WEAR AND TEAR’

Ordinary Namibians were aware of the lack of improvements, Melber says, and their discontent is evident from recent election results.

“The first signs of wear and tear in the Swapo hegemony became visible with the elections in November 2019 and November 2020, when dissatisfaction translated into a first decline of Swapo’s political control over the country’s governance.”

According to Melber: “In the absence of a more efficient policy coherence, which would be able to link the narrative of the Swapo government(s) with material delivery for the majority of the people and dismissing sufficient recognition of multiple identities in terms of political, cultural and ethnic background as well as other forms of deviating behaviour from the established norms and values defined by those in political power, social cohesion in Namibia remains superficial and less anchored than it claims to be.”

* Prof Henning Melber is also affiliated as director emeritus of the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, he is an extraordinary professor at the University of Pretoria and the University of the Free State, a senior research fellow at the Institute for Commonwealth Studies/University of London, as well as the president of the European Association of Development Research and Trading Institutes (EADI). He has been a member of Swapo since 1974.

Kommentaar

Republikein

Geen kommentaar is op hierdie artikel gelaat nie